Standard Viewing Conditions for

the

Graphic Arts (ISO 3664:2009)

Before you blame your proofing device or your pressroom or somebody or something because the color on that last job wasn't right - again- take a look at where you and your customers are making those color judgments. It might just be that you're seeing things "in a different light."

Color and density measurements play important roles in the process control of color reproduction, but they can't replace the human observer for final assessment of the color quality of complex images. In the color reproduction process, we commonly compare different kinds of originals and reproductions with one another for fidelity of color matching; e.g., color reflection artwork, photographic transparencies, photographic prints, off-press and on-press proofs, and press sheets all are commonly visually evaluated for their image and color quality or compared critically with one another for fidelity of color matching.

There is no doubt that the best viewing condition for visually assessing the color of a printed product, is the environment in which it will be finally seen. Where we know what this environment will be, and where it is practical to do so, the people in the production chain may sensibly agree to use this viewing condition to evaluate the final printed product. Unfortunately, this is usually not practical.

More importantly, though, such end-use viewing conditions don't allow us to make valid comparisons between the original artwork, photography, off-press proofs, etc., and the final printed sheet. This is because the color appearance of each of these materials is affected, often differently, by the light source and viewing conditions. To avoid miscommunication about color reproduction and processing, consistent viewing conditions must be used throughout the production chain.

The color and brightness of other objects and surfaces in the observer's field of view can also significantly influence his/her perception of the tone scale and color of a print or transparency. For this reason, ambient conditions, and the immediate surround conditions, of the viewing location also need to be controlled. In many situations, this is the role of the viewing booth. However, a viewing booth is not always requiredÑthere are many situations in graphic arts where a portion of a room or an open area can be established as a viewing area that meets the requirements.

The only way to ensure consistent viewing conditions, among all the players in the reproduction process, is to have a single recommendation everyone can aim toward. The current proposal for that single recommendation is ISO 3664, Viewing conditions for Graphic Technology and Photography.

Where Did We Get This Standard?

Prior to this new standard, viewing conditions were defined in a 1975 version of ISO 3664 called Photography-Illumination conditions for viewing color transparencies and their reproductions and an ANSI standard called PH2.30-1989 For Graphic Arts and Photography - Color Prints, Transparencies, and Photomechanical Reproductions - Viewing Conditions. These standards were similar but were not the same as each other.

In late 1994, under the auspices of

ISO/TC42,

a joint task force was created to revise the ISO standard. The task

force,

chaired by Tony Johnson of the U.K., was composed of members of ISO

Committees

TC42 (Photography), TC130 (Graphic technology) and TC6 (Paper, board

and

pulps). There was tacit agreement from members of the ANSI committee to

assist in the revision, with the goal of accepting the ISO document as

the ANSI standard. In 2009 ISO 3664 was published in its final version.

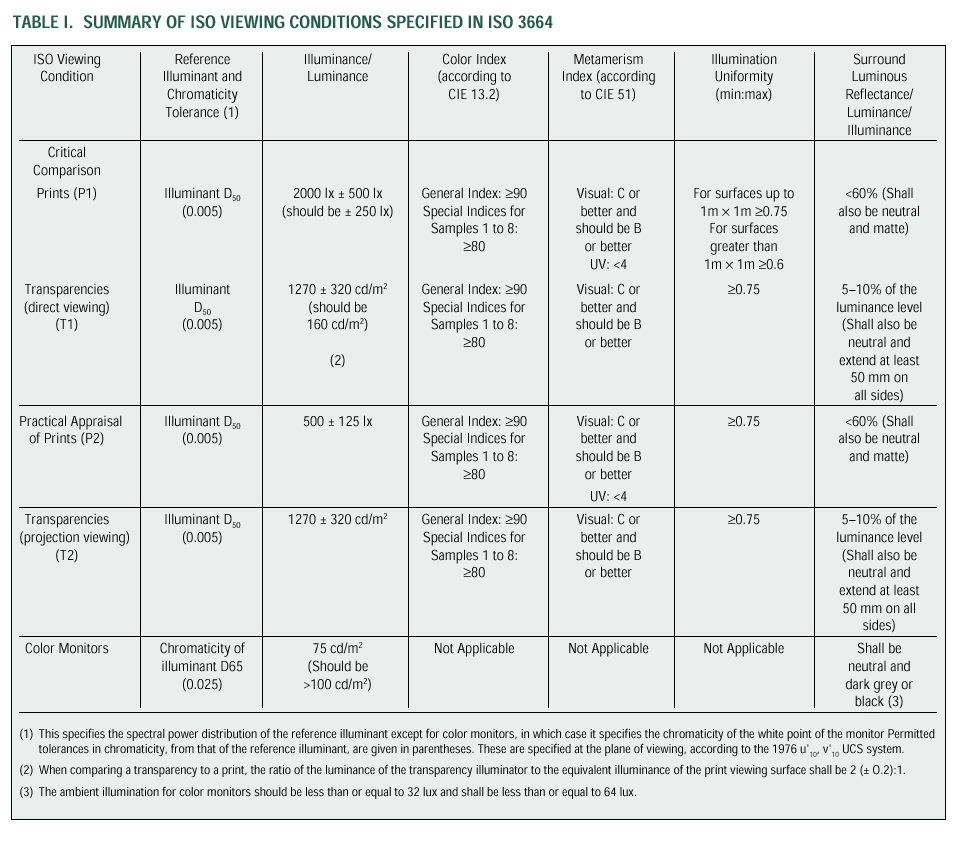

What Is Specified?

Several items are critical to ensure consistent viewing conditions throughout the graphic arts production chain. These are the:

Spectral power distribution of the illumination, Intensity and uniformity of the illumination, Backing and surround conditions (the viewing booth or illuminator environment), and Maintenance recommendations.

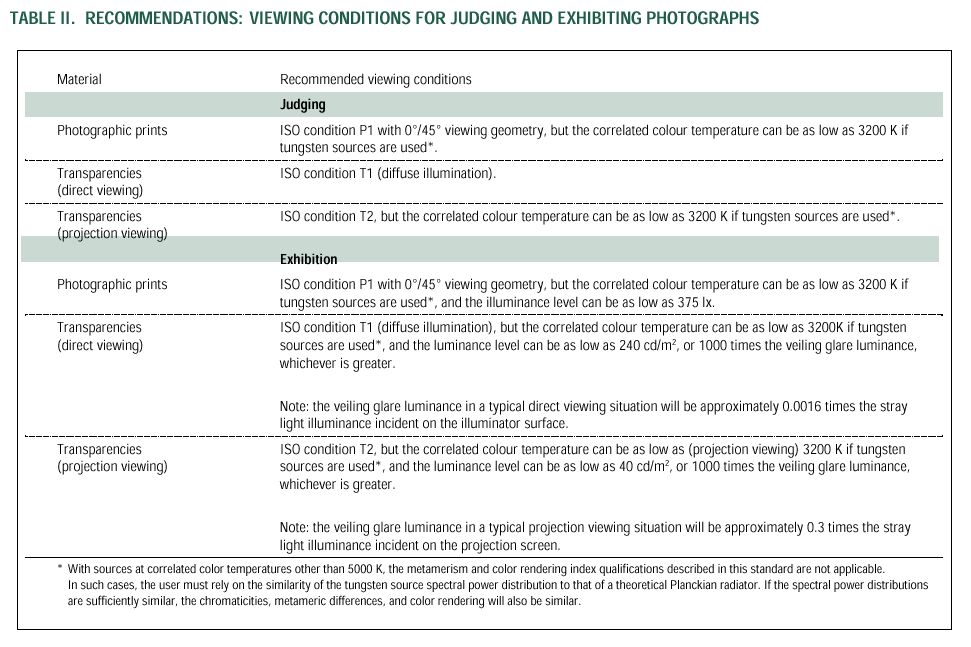

They are all included in ISO 3664. The standard also provides recommendations for the viewing conditions for images on color monitors and viewing conditions for the exhibition and judging of photographs. (This standard is intended to cover the needs of both the graphic arts and photographic industries.)

Illuminant Definition

The basic illuminant specified for viewing is (and has been for some time) something called CIE Illuminant D50. This defines the spectral distribution of daylight that has a correlated color temperature of 5000 Kelvin. Supposedly, one of the reasons D50 was picked originally was that, of the available CIE daylight illuminants, it comes closest to having equal energy in the blue, green, and red portions of the spectrum. It was kept in the current standard because it is the reference for most viewing booths in use today.

Unfortunately, there are no real lamps that exactly match CIE Illuminant D50. Manufacturers use various combinations of phosphors in fluorescent lamps and filters to create D50 simulators. Therefore, the standard must specify how closely a real viewing booth illuminator (a D50 simulator) matches the theoretical D50. In the prior standards the basic definition of the "goodness of the match" to D50 was a CIE procedure called Color Rendering Index or CRI. This compares the color of a set of standard samples under theoretically perfect D50 with their color under the actual illuminant. The degree to which they match is used as the index parameter.

This is fine if we are dealing with colors that have nice smooth reflectance curves and if UV brighteners are not an issue which is where we were back in 1975 when the previous draft of the ISO standard was written. This is not the case today.

Today, color imaging and proofing systems are using a host of new technologies to create images. Dye sublimation, thermal transfer, inkjet, and electrophotography are all producing an ever-increasing gamut of color. Many of these technologies achieve a color match to photography or ink on paper by using combinations of "cleaner" dyes that have much more abrupt transitions in their reflectance curves than the color that they are matching. This is called a metameric match (how that works is another whole article by itself). However, one of the side effects is that they are more sensitive to changes in the nature of the illumination. The real impact of this is that just using CRI is not enough anymore.

The new standard keeps the same CRI criteria but also introduces two new criteria called the visible and UV metamerism indexes. They are based on a CIE standard called CIE Publication No. 51, 1981A method for assessing the quality of daylight simulators for colorimetry. The indexes use more complex matching criteria, one for the visible and one for the UV portion of the spectrum, to further restrict the allowable differences between the actual spectral output of the D50 simulator and CIE Illuminant D50.

This means that viewing equipment meeting the new standard will provide more consistent viewing conditions and will be less susceptible to problems caused by either the new materials or fluorescence in the paper or inks. Fortunately, preliminary practical tests indicate that most of the better viewing equipment that meets the old standard will also meet the new standard. Earlier equipment that was marginal may have problems and need updatingÑit is too soon to tell what specific models will be acceptable and which will require additional work.

A GATF/RHEM Light Indicator gives a visual warning when color evaluations are taking place under lighting conditions that are inappropriate. The convenience of affixing this device directly to the proof makes it a positive reminder of the need to check viewing conditions. It is important to remember that the GATF/RHEM Light Indicator will not, and cannot, verify that the lighting conditions are properÑit is not sensitive enough for that purpose.

Intensity Levels

The new standard introduces two levels of illumination, a high level (P1) of 2000 ±500 lux for critical evaluation and comparison and a lower level (P2) of 500 ±25 lux for appraising the tone scale of an image under illumination levels similar to those under which it will be finally viewed. The higher level, which is the level included in the previous standards, is essential when making critical evaluations and comparisons, for example when comparing original artwork with proofs or when evaluating small color differences between proof and press sheet in order to control a printing operation.

Since, despite adaptation, the level of illumination significantly affects the appearance of an image, the lower level is required in order to appraise the image at a level more similar to that in which it will be finally viewed. Although it is recognized that quite a wide range of illumination levels may be encountered in practical viewing situations, the level chosen is felt to be fairly representative of the range we normally encounter.

The introduction of this lower level of illumination has created considerable discussion in some portions of the industry, and concerns have been raised about the possibility of confusion. To help alleviate these concerns the following caution has been inserted into the final version of the standard:

NOTE: "Critical comparison" is carried out under illumination levels that are considerably higher than those used for normal viewing. This is to ensure that subtle differences between two hard copy images, for instance a contract proof and a press sheet, can be easily distinguished. For this reason all comparisons between any two or more such images must be carried out under P1 conditions. However, evaluation of the tone reproduction and aesthetic quality of a single image, as it will be perceived by the reader of the print, is best judged under the final viewing to be used for that assessment. But where this is not known, or cannot be easily simulated, it is best to at least use illumination levels more typical of those used for normal viewing. Such a procedure will ensure, for example, that shadow detail is not lost to the viewer. For these applications P2 conditions should be used.

Here an experience that highlights the practical aspects of this issue:

"I was recently shown an image with a series of different highlight placements. The image contained some fine lace that was close to the color of the background. The selection I made looking at these in the office was not the same as the image I picked as most acceptable in the viewing booth. What looked good in the office was washed out in the booth. A short time later I was looking at a national ad for one of the large retail chains. It had a series of colored illustrations of black lawn mowers and grills against a dark background. My first reaction (at home in the easy chair) was - Who ever decided on these color separation aims? I can hardly see the image.- But, when I put the same ad in the viewing booth I could see into the shadows with no problem at all."

We have all seen these types of images. Be alert for possible examples and try it yourself.

Yes, we can take these images into a hallway, office, or some other area of lower level illumination to check on their appearance in addition to their match to the original in the viewing booth. But, such casual illumination is not controlled in either level or color characteristics. When we use such casual illumination with proofs, particularly some of the newer materials, we are going to be forced to adapt to color shifts as well. It is much better to define a lower level viewing condition so those things that match under the comparison standard (2000 lux) will also match under the lower level. In that way, tone reproduction judgments, can be made much more realistic and more practical at the same time. Most importantly, such judgment conditions will be reproducible between sitesÑsomething that we do not have now.

The standard also provides specifications for both projection and direct viewing of transparencies. For direct viewing, it specifies that the luminance at the center of the illuminated surface of a transparency illuminator is to be 1270 cd/m2 ±320 cd/m2. It goes on to specify that the surround needs to be at least 50 mm wide on all sides, appear neutral compared to the source, and have a luminance that is no more than 10% of that of the surface of the image plane of the illuminator. However, a transparency mounted with an opaque border may be viewed without removing the mount.

Viewing Environment

Because ambient conditions play such an important role in viewing, the new standard has included the following cautions:

The visual environment shall be designed to minimize interference with the viewing task. It is important to eliminate extraneous conditions that affect the appraisal of prints or transparencies and an observer should avoid making judgements immediately after entering a new illumination environment because it takes a few minutes to visually adapt to that new environment.

Extraneous light, whether from sources or reflected by objects and surfaces, shall be baffled from view and from illuminating the print, transparency, or other image being evaluated. In addition, no strongly coloured surfaces (including clothing) should be present in the immediate environment.

NOTE: The presence of strongly coloured objects within the viewing environment is a potential problem because they may cause reflections, which cannot easily be baffled. Walls, ceiling, floors, and other surfaces which are in the field of view shall be baffled or coloured a neutral matte grey, with a reflectance of 60% or less.

The new standard also specifies that the surround and backing need to be neutral and matte and extend beyond the materials being viewed on all sides by at least one-third of their dimension. The surround must have a reflectance of less than 60% and preferably less than 20%. It does note that where objects are being compared, they may be positioned edge to edge.

Maintaining Light Sources

Unfortunately, the typical user of a viewing booth does not have access to the instruments necessary to measure either the illumination level or the spectral distribution of energy. As a result, the most critical maintenance issue is to change bulbs frequently enough and on a regular schedule.

The standard requires the manufacturers to "specify the average number of hours during which the apparatus is expected to remain within specification" and cautions users to "make every effort to comply with this, unless it can be otherwise demonstrated that the equipment remains within tolerance." It suggests including a time-metering device or some other mechanism for indicating degradation in the viewing apparatus.

Some manufacturers recommend 2500/5000 hours of bulb life, or one year, as a good interval between bulb changes. It goes without saying that the surfaces of a viewing booth should be kept clean and free of clutter.

Monitor Viewing Conditions

Until now, the industry has not had any recommended conditions for viewing images on a monitor. This was not a problem as long as people were not trying to make final judgments based on a soft display. We won't attempt to argue whether such judgments are valid, smart, or proper. Certainly, a first step in attempting to achieve some degree of consistency is to define a recommended viewing condition. The new standard contains specifications for the viewing of a monitor independent of any form of hard copy. Thus, these specifications can be seen as being primarily relevant where successive viewing of hard copy and soft copy takes place. Another standard, ISO 12646 Graphic Technology-Colour proofing using a colour monitor, currently in preparation, is being developed by TC130 to provide a more detailed recommendation where direct comparison is required.

The specifications in ISO 3664 include the following requirements:

The chromaticity of the white displayed on the monitor should approximate that of D65. The luminance level of the white displayed on the monitor shall be greater than 75 cd/m2 and should be greater than 100 cd/m2. When measured in any plane around the monitor or observer, the level of ambient illumination shall be less than 64 lux and should be less than 32 lux. The color temperature of the ambient illumination shall be less than or equal to that of the monitor white point. The area immediately surrounding the displayed image shall be neutral, preferably grey or black to minimize flare, and of approximately the same chromaticity as the white point of the monitor. The monitor shall be situated so there are no strongly colored areas (including clothing) directly in the field of view or which may cause reflections in the monitor screen. Ideally all walls, floors, and furniture in the field of view should be grey and free of any posters, notices, pictures, wording, or any other object which may affect the viewer's vision. All sources of glare should be avoided since they significantly degrade the quality of the image. The monitor shall be situated so that no illumination sources such as unshielded lamps or windows are directly in the field of view or are causing reflections from the surface of the monitor.

These are things that are seldom done today. Having clearly specified goals, however, should allow us to move one more step forward in the communication of the appearance of color images on a monitor.

Other Items ISO 3664 also includes a section on test conditions and an annex that describes some of the experimental data used to evaluate the validity of the standard.

Because "the subjective impression produced by photographs that are judged for contests or juried exhibitions is of particular importance," an informative annex in the standard provides "Guidelines for the Judging and Exhibiting of Photographs" (remember, this is a joint graphic arts and photographic standard).

Conclusions

As the demand for process color printing continues to rise and customers expect greater color consistency and quality, the need for standard viewing conditions for color appraisal becomes more acute. The graphic arts industry is a highly segmented manufacturing process with many individuals, frequently from different companies, involved in the reproduction of color images. The nature of color perception makes the communication process even more difficult.

It is essential for the visual communication process to operate under a standard set of illumination conditions. The new version of ISO 3664:2009, provides a thorough and clearly defined set of viewing conditions for the graphic arts. Conscientious use of viewing equipment that meets the ISO specifications helps to eliminate confusion and mistakes caused by uncontrolled lighting conditions during critical color decisions.

by Richard W. Harold and David Q. McDowell

• GATFWorld magazine January/February 1999

.

For more information please contact:

.