RW

Info:

RW

Info:

How To: Create Stunningly Realistic High Dynamic Range

Photographs

In the right hands, high dynamic range imaging can blend multiple

exposures of the same scene to more closely reproduce what your eye can

see. Here's how to do HDR the right way.

So when should you use HDR? It's simple: when you're trying to capture

a scene with a wide range between its lightest and darkest areas (aka

dynamic range) as accurately as possible. Your camera's sensor can only

capture a small portion of the light that your eye can take in and

process, so to make up for that, HDR images are created by combining

the pixel information from several pictures into one 32-bit

Voltron-file that contains the full dynamic range of each of the

individual shots used to create it.

Take this range of shots of the Cairo skyline I took last week from the

top of the highest minaret of the Al Azhar mosque in that lovely city.

Neither one of the three accurately exposes the whole scene—in the shot

that captures the sky correctly, the buildings below are too dark, and

when the buildings are exposed accurately, the sun behind the clouds

gets blown out, losing all detail. So this is the perfect situation for

an HDR image.

But in many cases rightfully, HDR has a reputation as a gimmick that

can easily be abused to turn your photos into dreadful, over-saturated,

tacky looking messes of clown vomit. But if your main intent is to

accurately capture a scene as your eye sees it, you can come away with

some believable but still otherworldly (for a photograph, in a good

way) images. In the end, it all comes down to personal preference; you

may think my shot above looks like garbage. That's cool, save your

comments, photo snob trolls. You're free to make your shots look

however you want, and here's the best way I've found to do just that.

What You'll Need:

• A camera that has auto exposure bracketing (not essential,

but without it, you'll have to set the range of exposures manually and

will need a tripod). At the very least you'll need manual exposure

controls.

• Photoshop CS2 or higher (you can also use specialized HDR software

like Photomatix, but for this guide I'm using Photoshop CS4).

• Some knowledge of curves and histograms in Photoshop.

Take Your Shots

As mentioned before, you'll get the most bang for your HDR buck

with scenes that have both extremely bright and extremely dark areas of

interesting detail to bring out. So choosing the right scene is an

obvious first step.

1. Set your camera to auto exposure bracketing mode, which takes three

(usually) sequential shots at three different exposure levels: one

correctly exposed, one overexposed, and one underexposed. You can

usually specifiy the amount of exposure stops to under- and

overexpose—you probably want the maximum range, which is usually a full

two stops in either direction.

2. You want to take the three shots in the quickest succession possible

since we'll be merging them later and you don't want moving objects to

foul that up. So turn your camera on burst shooting where possible and

hold down the button, firing off three quickies without moving. This is

where you'll need a tripod for cameras without AEB to keep the shots

uniform.

Note: If you can, shoot in RAW. Photoshop can handle RAW files just

fine, and the extra exposure information within compared to JPEG will

make your HDR images all the more juicy. Also, the more source images

you have the better, so if you do have a tripod and are shooting an

immovable scene, bringing more than 3 images to your HDR file will only

give you more detail to work with.

Create Your HDR Image

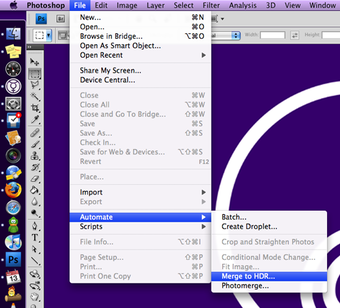

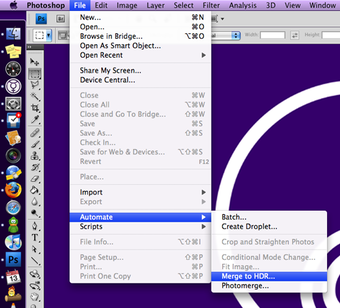

3. In Photoshop, go to File -> Automate -> Merge to HDR. Select

your three images, click "Attempt to Automatically Align Source Images"

if you think they may be slightly crooked, and then hit OK. Photoshop

will chew on them for a while and then present you with your 32-bit HDR

image.

You may notice that the file you have now doesn't look so hot. That's

because a 32-bit HDR image isn't useful in itself unless you have a

$50,000 HDR monitor. To look good on your screen and on paper, it must

now be "tone mapped" into an 8-bit image that selectively uses parts

from each exposure to accurately represent the scene.

4. Before we head to tone mapping, save your HDR as a 32-bit Portable

Bit Map file so you can start fresh again if need be.

Tone Mapping Your Image

How you tone map the HDR file determines whether your result

will look great or like the aforementioned clown vomit. We're using

Photoshop here because it's more closely tuned, in my opinion, to

achieving real-world results than HDR-specific software like

Photomatix. Here, though, personal taste is everything, so if you like

your images more or even less saturated and otherworldly than I do

here, feel free to experiment, of course. They're your photos! It also

helps to keep an eye on your originals as you're doing this to make

sure you don't stray too far from reality.

To become a skilled HDR jockey in the tone mapping department, you'll

need to be at least a little bit familiar with two fundamentals of

digital imaging that tend to hide in the background for most users—the

scary-looking graphs known as histograms and curves, both of which look

like they belong in your school text book.

But no need to cower in fear! Watch this video right now to get the

basic gist of curves (and also, essentially, histograms).

Now, armed with that knowledge, to tone-mapping!

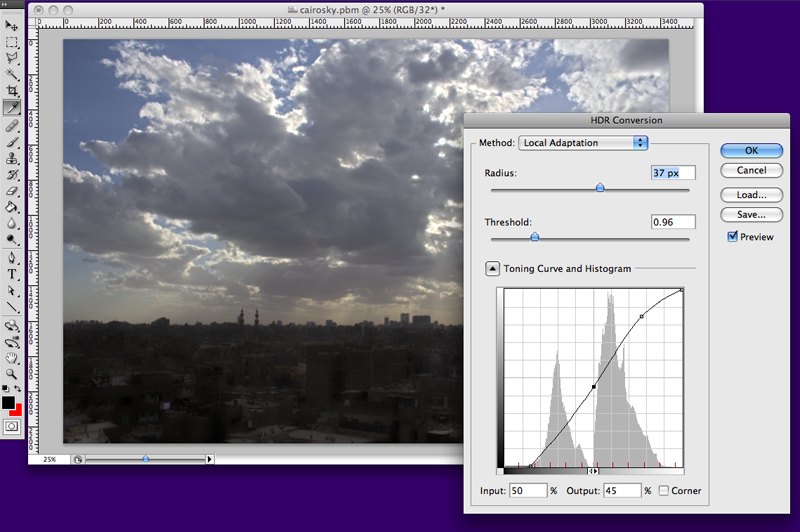

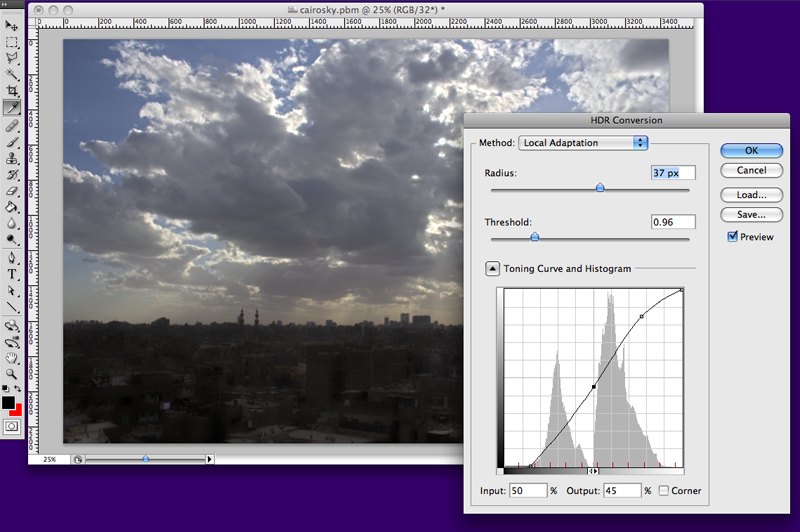

5. With your 32-bit HDR file open, go to Image -> Mode -> 8

Bits/Channel. This will bring up the tone mapping window, which has

four options in the drop-down: Exposure and Gamma, Highlight

Compression, Equalize Histogram and Local Adaptation. The first three,

to varying degrees, are automatic settings. To say I understand the

specific differences between all four would be lying, but I do know

this: Local Adaptation is the only one that lets you manually futz with

the image curve, giving you the most creative control. Choose that one

(but feel free to experiment with the others, of course).

6. Here's where things get kind of abstract. If you watched your

tutorial video, you'll know you want to use the eyedropper tool to

isolate areas of the image you want to work with, then create an anchor

point and move that section of the curve into the ligher or darker area

of the graph. You can start with the easiest adjustment, which is

dragging the lower-left portion of the curve to where the histogram

begins—this will make the darkest parts of your image pure black, which

you want for good contrast.

7. Your next goal should be to fiddle with a point higher on the curve

to make your whites whiter. So grab a point up there and move it into

the top portion of the graph until the whites are to your liking in the

live preview.

8. And finally, choose a point in the middle and work the midtones.

Again, preference is key, but you'll want something that, in the end,

represents a classic S-curve for the best contrast. In the end, you

want an image that has black blacks, white whites (but few to zero

completely washed out areas), and detail through the midrange. Your

image may still look not so good when your curve is done, but that's OK.

9. The last step in the tone mapping process is to mess with the good

ol' Radius and Threshold sliders. Again, like many things in Photoshop,

I have no idea exactly what's being jiggered here, but these

essentially control how HDR-ed out your HDR images will look, if that

makes sense. The wrong setting will peg the image's edge detail,

resulting in some yucky looking mess. I like to keep a little bit of

blown-out highlights in the image too, to remind everyone it's still a

photo.

So fiddle with these sliders until the live preview looks good in your

esteemed opinion. Again, your image won't look perfect, even now. The

object here is to strike the right balance between detail and a natural

look.

Toning Your Image

Now you have a good old fashioned 8-bit image that contains

some elements of all three of your original source files, tone mapped.

The final step is applying some of Photoshop's basic tools used for any

photo in order to bring out the most detail possible.

10. First, Levels. Even though you set contrast with your tone curve,

you may still be able to fine tune it with levels. So under Image ->

Adjustments -> Levels, make sure the black and white sliders are

aligned with the left and right edges of your histogram mountain to the

extent that it pleases you.

11. Next, Image -> Adjustments -> Shadows/Highlights, one of

Photoshop's most magical tools. Here is where the areas of your image

that previously looked too dark will reveal their glorious hidden

detail. Slowly raise the Amount and Tonal Width sliders under Shadows

until the detail comes out, but not too far into ugly boosted-out

territory. Do the same for Highlights.

12. And last, Image -> Adjustments -> Hue/Saturation, where you

probably want to boost the Saturation just a little bit to get the

colors popping to your liking.

And that's it! You should now have an HDR image that captures that

amazing scene like you remembered it, without the clown vomit!

Return

to - Regresar a rainerwagner.com

© 2010/2022 Copyright by rainer wagner

RW

Info:

RW

Info: RW Info: